AYE introduced me to the Satir Change Model. I remember feeling anxious about attending because it’s not one of those sit-in-front-of-a-projector conferences, it’s an experiential learning experience.

The first session I attended was about managing change and it was hosted by Steve Smith. Since I’ve written about this before, I’ll give you the reader’s digest version. This post will make more sense if you have a basic understand of the “J curve” that is the Satir Change Model.

Steve broke us into groups, Old Status Quo, Foreign Element, Chaos, New Status Quo. He selected a “star” and the objective of the session was for the Old Status Quo (the group I was in) to keep the star in one corner of the room. The objective of the New Status Quo was to get the star to move to the opposite corner of the room. Chaos’ responsibility was to disrupt everything and the Foreign Element’s responsibility was to trigger the disruption.

Long story short, here are 70 or so highly enlightened Agile practitioners, for the most part, building walls out of tables and chairs, pushing and shoving each other, tossing chairs aside and trying to meet their groups objective. The experience had escalated to the point where Steve had to interject and yell “STOP!”. If you’ve never met Steve, he’s about 6 foot 4 and has a deep booming voice so that snapped all of us back into reality.

Over the last couple of years I’ve spent most of my time studying and experimenting with change management, organizational change and neuroscience tools, methods and techniques to try and figure out why there is so much emphasis on managing change and if it’s even possible to “manage change”.

The message at AYE was quite clear to me. You cannot control change and that, to me, is implied with managing change.

I have seen too many instances of plan-driven approaches to change fail when they’re driven by budgets and timelines. They’re driven this way because executives need to budget for a change team which means the change team has to come up with a plan that makes the executives feel like everything is under control yet the change team knows the plan is a pile of, um, you get the idea. Not a great place to be starting from.

A couple of weeks ago at the Art and Science of Change in Toronto I gained some insights into how plan-driven the traditional change management world is. To be clear, I am using the term “change” in the context of transformational change. There was much talk about 12-step change programs, driven by schedules and budget, as well as talk of ROI and other non-sense (to me!) that cannot possibly deal with the complexity of transformational change.

There is no shortage of change methods available and many studies from organizations that developed these methods show a 30% success rate yet they still cling to plan-driven approaches to change all the while wondering why it doesn’t work. And these are some incredibly smart people I’m talking about.

So how does transformational change start? From my experiences it’s usually brought in by management or executives with a top-down approach. I’ve seen bottom-up approaches as well but for this post I’ll focus on large-scale transformational change brought in from the top.

The executive initiates the change, the change team comes up with a nice plan, wiki, intranet and newsletter based on some ‘best practice’ and the change plan starts.

The problem is, there is no ‘start’ to change. Once the rumour mill is ignited with this transformational change, the change team is working on the plan while the worker bees are already freaking out about the impending change. The organization is already in chaos before the ‘change project’ has even started.

The change team then executes the plan that was developed at a point in time that is no longer relavent. I’ve been tinkering with a visual to explain this and, as usual, I recently found out something already exists. It’s called the Fragmentation Prime.

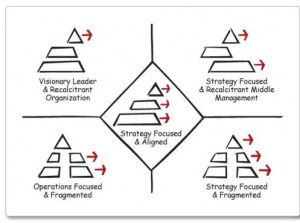

The change plan breaks down when there is fragmentation across different levels of the organization. I’ve worked in organizations with visionary executive leadership that were too far ahead of the rest of the organization. I’ve also worked in organizations with the opposite fragmentation. Teams are kicking ass with Agile and executives are completely un-aware or they get wind of it and try to control and standardize the new process.

I have ‘aha!’ moments to this day from AYE 4 years ago. Managers in today’s organizations are not change agents, they don’t have the skills, experience or education to execute change because that’s not their focus. Their focus is expertise and experience in their domain whether it be testing, development, infrastructure or what-have-you. They’re simply not equipped with the tools today’s change managers, organizational development and (some) agile coaches have. This isn’t a knock on managers, I’ve been in those situations many years ago and remember feeling terrible that I had no idea how to deal with change and how it affects people. I used all the ass-backwards performance models and scientific management styles that are irrelevant in today’s knowledge work.

Compounding the problem is when the executive that initiated the change leaves within a year or two and their successor decides Agile wasn’t the right thing and goes back to the old way. In that case, managers and staff are more confused and develop an apathetic attitude over time because they know whatever change is mandated will die when the initiating executive leaves. I’d be interested to find out the average tenure of a CTO or CIO, I suspect the churn is more frequent than managers or staff.

When it comes to change, some take the perspective of changing behaviours or developing a new mindset or changing the culture. Some take a brain-based approach (Results Coaching) to organizational change by focusing on developing capability with managers. Some take the approach of using frameworks like the 4 Disciplines of Execution or Rockefeller Habits for creating focus and direction. Some use traditional, linear and plan-driven methods such as Prosci’s ADKAR or McKinsey’s 7S. Some say Kanban or Scrum is the best and try to create a cookie-cutter approach to change.

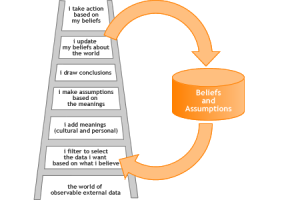

There are no shortage of approaches to how to bring about transformational change but you’ll discover that people are fans of what they know and are quick to dismiss other ideas and approaches. Looking at Jung’s Ladder of Inference it’s possible to see why that’s the case. People attach beliefs to their method of choice and filter out possibilities from other methods. It could be their method of choice worked once or their method of choice sets their confirmation bias light in their brain explode. We are all biased in some way so this is natural. The key is to become aware of your own bias‘! As an example you’ve probably seen debates in the Agile/Lean communities where one camp says Kanban is the best and everything else sucks and the other camp says Kanban sucks and Scrum is the best. That may be true from their perspective but that doesn’t make it a universal truth. That phenomena is called yelling from the top of the ladder.

It’s also important to consider how people process change and the temperament of the change agent and change sponsors. To generalize, if your change sponsor has a strong Guardian (SJ) preference, they may be more inclined to push a plan-driven approach because that’s their preference. Using feedback-driven approaches to change by learning about systems thinking and complexity science might not make a lot of sense to someone with a strong Guardian preference because it may appear to be too passive and the change team is sitting around waiting for something to happen or waiting for people to ask for help.

We must balance the art and science of change and use different approaches from a variety of methods because of these reasons:

- Complexities of organizations (systems thinking, complexity science)

- How people process change (Satir)

- Our own bias’ (there are hundreds of them)

- How people’s preferences contribute to the complexity of change (Keirsey – Temperaments)

- How change agents are biased (Jung – Ladder of Inference)

- What neuroscience tells us (SCARF – David Rock)

These are reasons why I’m a proponent of Lean Change. Lean Change is method agnostic although I supposed you can call Lean Change it’s own method. Lean Change takes the customer development aspect of Lean Startup and applies it to change.

Can Lean Change help “manage change better”? Maybe, maybe not. At the end of the day people cannot create a method or process that is more complex than the human brain which is why Lean Change minimizes process, isn’t linear and is completely feedback-driven while allowing you to pluck ideas from different methods. Check out these resources about Lean Change:

Lean Change Lightening Talk by Jeff Anderson at the Toronto Agile Tour

Lean Change at Agile 2013

Back to the question, can change be managed? In the traditional change management sense? No. Change agents must involve the people being asked to change in the change execution. People don’t like to be fixed, and forcing change on people generates a threat response which manifests itself as resistance.

Remember, Darwin said the species that survive aren’t the smartest or strongest, they’re the ones that learn how to adapt.